Category Archives: Uncategorized

ICO newsletter: direct marketing, but no need to “reconsent”

I suspect everyone is now fed up to the back teeth of emails from long-forgotten and sometimes never-known businesses and organisations claiming they need us to renew our consent to receive electronic marketing from them. In many cases we never wanted the marketing in the first place and therefore almost certainly never consented to receive it, according to how “consent” has been construed in the operative law (the Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA), and, specifically, the Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) Regulations 2003 (PECR)). Everyone is probably equally fed up with similar emails from businesses and organisations we do have a relationship with, and from whom we do want to hear. I’m not going to rehash the law on this – I’ve written and commented multiple times elsewhere (search “Jon Baines +banging head against a brick wall”), as have other, more sage people (try Tim Turner, Adam Rose or Matt Burgess).

But I did notice that the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) recently issued a broadly helpful corrective to some of the misinformation out there. I say “broadly helpful” because it is necessarily, and probably correctly, cautious about giving advice which could be potentially interpreted as “do nothing”. Nonetheless, it makes clear that in some cases, doing nothing may be precisely the right thing to do: although the definition of “consent” from the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will drop into PECR, replacing the definition which currently applies (the one at section 11 (3) of the DPA), this does not represent a significant reconfiguring. In general, if you had proper consent before GDPR, you’ll have proper consent under GDPR, and if you didn’t, well, you probably don’t have consent to send an email asking for consent.

Even though the ICO corrective was welcome, I’d actually already begun some slightly mischievous digging.

For a number of years, through various email addresses, I have subscribed to the ICO’s email newsletter (I invite thoughts, through the “comments” function on this blog, about the adequacy of the privacy notice given when one signs up to it, but this post is not directly about that). All the nonsense emails flying round got me to thinking – the ICO newsletter is probably “direct marketing” according to the law and the ICO’s own guidance, and when it is sent to an “individual subscriber” the PECR consent requirements kick in. So, I wondered, had the ICO reviewed whether it needed to get “GDPR-standard consent”, at least from those individual subscribers?

The answer, in response to my request for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000, is yes – the ICO have reviewed, and no, they don’t think they need to “reconsent”.

They’ve told me that

We have reviewed our e-newsletter and consent as part of our preparations for the requirements of GDPR…we do think our newsletter constitutes direct marketing [but we] don’t think we need to seek re-consent from individuals who have already consented to receive the newsletter. The newsletter is only sent to people who asked to receive it, this was done on an opt in basis on the back of a clear question asked separately from other information. We have a record of the date they asked to receive the newsletter. There is an unsubscribe option at the end of each newsletter and we log when people tell us they don’t want to receive it anymore – we’ve reviewed that process to make sure it is robust.

Pretty clear, I think.

I post their response here in the hope it might assist those who are in a similar position are struggling to understand whether they need to send another of those stupid “reconsent” emails flying around.

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.

Filed under Uncategorized

When will it all stop?

I saw two iterations of the same erroneous statement about the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) this morning, and it’s instructive to compare them.

One was in a Times article by journalist Danny Fortson. This said:

[Under GDPR] organisations large and small will have to ask for new permission to keep personal details on file

The other was contained in a brief twitter exchange which I barged into, in which a personal trainer revealed that a “GDPR consultant” had told her that she

had to regain all [client] details and destroy all the previously held info

I haven’t got anything profound to say here – just three observations: 1) GDPR absolutely does not expressly require businesses to do anything about client or customer data already held, let alone contact those people to get their consent 2) there is some shockingly bad advice about GDPR apparently being promulgated by people purporting to be competent to give it 3) there is a rather toxic feedback loop by which this shockingly bad advice is repeated in the media, and then picked up by others.

I hope it will all calm down after 25 May. And I also hope that decent people running decent businesses don’t get permanently harmed by this situation.

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.

Filed under Uncategorized

Data protection and fake pornography

Wired’s Matt Burgess has written recently about the rise of fake pornography created using artificial intelligence software, something that I didn’t know existed (and now rather wish I hadn’t found out about):

A small community on Reddit has created and fine-tuned a desktop application that uses machine learning to morph non-sexual photos and transplant them seamlessly into pornographic videos.

The FacesApp, created by Reddit user DeepFakesApp, uses fairly rudimental machine learning technology to graft a face onto still frames of a video and string a whole clip together. To date, most creations are short videos of high-profile female actors.

The piece goes on to discuss the various potential legal restrictions or remedies which might be available to prevent or remove content created this way. Specifically within a UK context, Matt quotes lawyer Max Campbell:

“It may amount to harassment or a malicious communication,” he explains. “Equally, the civil courts recognise a concept of ‘false privacy’, that is to say, information which is false, but which is nevertheless private in nature.” There are also copyright issues for the re-use of images and video that wasn’t created by a person.

However, what I think this analysis misses is that the manipulation of digital images of identifiable individuals lands this sort of sordid practice squarely in the field of data protection. Data protection law relates to “personal data” – information relating to an identifiable person – and “processing” thereof. “Processing” is (inter alia)

any operation…which is performed upon personal data, whether or not by automatic means, such as…adaptation or alteration…disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available…

That pretty much seems to encapsulate the activities being undertaken here. The people making these videos would be considered data controllers (persons who determine the purposes and means of the processing), and subject to data protection law, with the caveat that, currently, European data protection law, as a matter of general principle, only applies to processing undertaken by controllers established in the European Union. (In passing, I would note that the exemption for processing done in the course of a purely personal or household activity would not apply to the extent that the videos are being distributed and otherwise made public).

Personal data must be processed “fairly”, and, as a matter of blinding obviousness, it is hard to see any way in which the processing here could conceivably be fair.

Whether victims of this odious sort of behaviour will find it easy to assert their rights, or bring claims, against the creators is another matter. But it does seem to me to be the case here, unlike in some other cases, that (within a European context/jurisdiction) data protection law potentially provides a primary initial means of confronting the behaviour.

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.

Filed under Data Protection, Europe, fairness, Uncategorized

An enforcement gap?

ICO wants 200 more staff for GDPR , but its Board think there’s a risk it will instead be losing them

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is, without doubt, a major reconfiguring of European data protection law. And quite rightly, in the lead-up to its becoming fully applicable on 25 May next year, most organisations are considering how best they can comply with its obligations, and, where necessary, effecting changes to achieve that compliance. As altruistic as some organisations are, a major driver for most is the fear that, under GDPR, regulatory sanctions can be severe. Regulators (in the UK this is the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)) will retain powers to force organisations to do, or to stop, something (equivalent to an enforcement notice under our current Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA)), but they will also have the power to levy civil administrative fines of up to €20 million, or 4% of annual global turnover. Much media coverage has, understandably, if misleadingly, focused on these increased “fining” powers (the maximum monetary under the DPA is £500,000). I use the word “misleadingly”, because it is by no means clear that regulators will use the full fining powers available to them: GDPR provides regulators with many other options (see Article 58) and recital 129 in particular states that measures taken should be

appropriate, necessary and proportionate in view of ensuring compliance with this Regulation [emphasis added]

Commentators stressing the existence of these potentially huge administrative fines should be referred to these provisions of GDPR.

But in the UK, at least, another factor has to be born in mind, and that is the regulator’s capacity to effectively enforce the law. In March this year, the Information Commissioner herself, Elizabeth Denham, told the House of Lords EU Home Affairs Sub-Committee that with the advent of GDPR she was going to need more resource

With the coming of the General Data Protection Regulation we will have more responsibilities, we will have new enforcement powers. So we are putting in new measures to be able to address our new regulatory powers…We have given the government an estimate that we will need a further 200 people in order to be able to do the job.

Those who rather breathlessly reported this with headlines such as “watchdog to hire hundreds more staff” seem to have forgotten the old parental adage of “I want doesn’t always get”. For instance, I want a case of ’47 Cheval Blanc delivered to my door by January Jones, but I’m not planning a domestic change programme around the possibility.

In fact, the statement by Denham might fall into a category best described as “aspirational”, or even “pie in the sky”, when one notes that the ICO Management Board recently received an item on corporate risk, the minutes from which state that

Concern was expressed about the risk of losing staff as GDPR implementation came closer. There remained a risk that the ICO might lose staff in large numbers, but to-date the greater risk was felt to be that the ICO could lose people in particular roles who, because of their experience, were especially hard to replace.

The ICO has long been based in the rather upmarket North West town of Wilmslow (the detailed and parochial walking directions from the railway station to the office have always rather amused me). There is going to be a limited pool of quality candidates there, and ICO pays poorly: current vacancies show case officers being recruited at starting salary of £19,527, and I strongly suspect case officers are the sort of extra staff Denham is looking at.

If ICO is worried about GDPR being a risk to staff retention (no doubt on the basis that better staff will get poached by higher paying employers, keen to have people on board with relevant regulatory experience), and apparently can’t pay a competitive wage, how on earth is it going to retain (or replace) them, and then recruit 200 more, from those sleepy Wilmslow recruitment fairs?

I write this blogpost, I should stress, not in order to mock or criticise Denham’s aspirations – she is absolutely right to want more staff, and to highlight the fact to Westminster. Rather, I write it because I agree with her, and because, unless someone stumps up some significant funding, I fear that the major privacy benefits that GDPR should bring for individuals (and the major sanctions against organisations for serious non-compliance) will not be realised.

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.

Filed under Data Protection, enforcement, GDPR, Information Commissioner, Uncategorized

Making even more criminals

Norfolk Police want your dashcam footage. Do you feel lucky, punk?

I wrote recently about the change to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) registration process, which enables domestic users of CCTV to notify the ICO of that fact, and pay the requisite fee of £35. I noted that this meant that

it is the ICO’s apparent view that if you use CCTV in your household and capture footage outside the boundaries of your property, you are required to register this fact publicly with them, and pay a £35 fee. The clear implication, in fact the clear corollary, is that failure to do so is a criminal offence.

I didn’t take issue with the correctness of the legal position, but I went on to say that

The logical conclusion…here is that anyone who takes video footage anywhere outside their home must register

I even asked the ICO, via Twitter, whether users of dashcams should also register, to which I got the reply

If using dashcam to process personal data for purposes not covered by domestic exemption then would need to comply with [the Data Protection Act 1998]

This subject was moved from the theoretical to the real today, with news that Norfolk Constabulary are encouraging drivers using dashcams to send them footage of “driving offences witnessed by members of the public”.

Following the analyses of the courts, and the ICO, as laid out here and in my previous post, such usage cannot avail itself of the exemption from notification for processing of personal data “only” for domestic purposes, so one must conclude that drivers targeted by Norfolk Constabulary should notify, and pay a £35 fee.

At this rate, the whole of the nation would eventually notify. Fortunately (or not) the General Data Protection Regulation becomes directly applicable from May next year. It will remove the requirement to give notification of processing. Those wishing, then, to avoid the opprobrium of being a common criminal have ten months to send their fee to the ICO. Others might question how likely it is that the full force of the law will discover their criminality, and prosecute, in that short time period.

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.

Filed under Data Protection, GDPR, Information Commissioner, police, Uncategorized

Making criminals of us all

The Information Commissioner thinks that countless households operating CCTV systems need to register this, and pay a £35 fee for doing so. If they don’t, they might be committing a crime. The Commissioner is probably mostly correct, but it’s a bit more complex than that, for reasons I’ll explain in this post.

Back in 2014, to the surprise of no one who had thought about the issues, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) held that use of domestic CCTV to capture footage of identifiable individuals in public areas could not attract the exemption at Article 3(2) of the European data protection directive for processing of personal data

by a natural person in the course of a purely personal or household activity

Any use of CCTV, said the CJEU, for the protection of a house or its occupiers but which also captures people in a public space is thus subject to the remaining provisions of the directive:

the operation of a camera system, as a result of which a video recording of people is stored on a continuous recording device such as a hard disk drive, installed by an individual on his family home for the purposes of protecting the property, health and life of the home owners, but which also monitors a public space, does not amount to the processing of data in the course of a purely personal or household activity, for the purposes of that provision

As some commentators pointed out at the time, the effect of this ruling was potentially to place not just users of domestic CCTV systems under the ambit of data protection law, but also, say, car drivers using dashcams, cyclists using helmetcams, and many other people using image recording devices in public for anything but their own domestic purposes.

Under the directive, and the UK Data Protection Act 1998, any data controller processing personal data without an exemption (such as the one for purely personal or household activity) must register the fact with the relevant supervisory authority, which in the UK is the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). Failure to register in circumstances under which a data controller should register is a criminal offence punishable by a fine. There is a two-tier fee for making an entry in the ICO’s register, set at £35 for most data controllers, and £500 for larger ones.

For some time the ICO has advised corporate data controllers that if they use CCTV on their premises they will need to register:

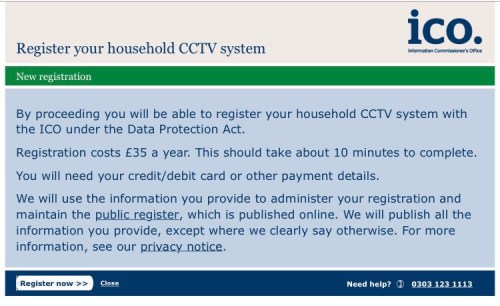

But I recently noticed that the registration page itself had changed, and that there is now a separate button to register “household CCTV”

If one clicks that button one is taken to a page which informs that, indeed, a £35 fee is payable, and that the information provided will be published online

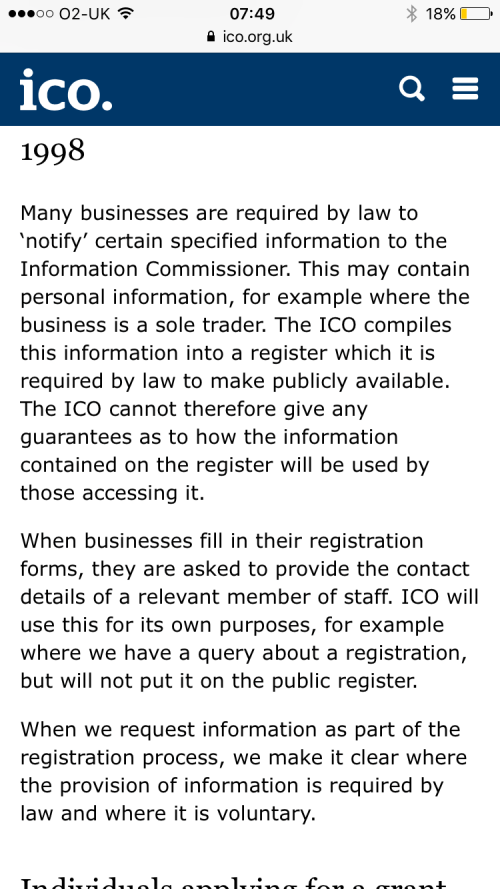

There is a link to the ICO’s overarching privacy notice [ed. you’re going to have to tighten that up for GDPR, guys] but the only part of that notice which talks about the registration process relates only to “businesses”

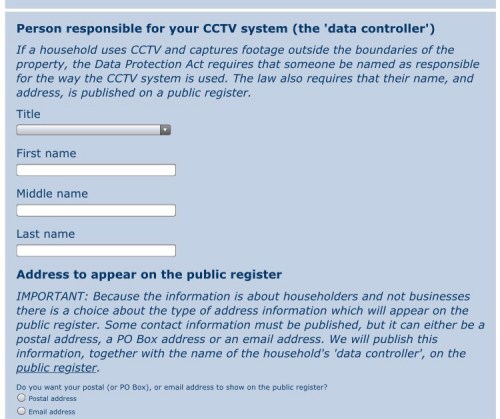

Continuing the household CCTV registration process, one then gets to the main screen, which requires that the responsible person in the household identify themselves as data controller, and give either their household or email address for publication

What this all means is that it is the ICO’s apparent view that if you use CCTV in your household and capture footage outside the boundaries of your property, you are required to register this fact publicly with them, and pay a £35 fee. The clear implication, in fact the clear corollary, is that failure to do so is a criminal offence.

(In passing, there is a problem here: the pages and the process miss the point that for the registration to be required, the footage needs to be capturing images of identifiable individuals, otherwise no personal data is being processed, and data protection law is simply not engaged. What if someone has installed a “nest cam” in a nearby wooded area? Is ICO saying they are committing a criminal offence if they fail to register this? Also, what if the footage does capture identifiable individuals outside the boundaries of a household, but the footage is only taken for household, rather than crime reduction purposes? The logical conclusion of the ICO pages here is that anyone who takes video footage anywhere outside their home must register, which contradicts their guidance elsewhere.)

What I find particularly surprising about all this is that, although fundamentally it is correct as a matter of law (following the Ryneš decision by the CJEU), I have seen no publicity from the ICO about this pretty enormous policy change. Imagine how many households potentially *should* register, and how many won’t? And, therefore, how many the ICO is implying are committing a criminal offence?

And one thing that is really puzzling me is why this change, now? The CJEU ruling was thirty months ago, and in another eleven months, European data protection law will change, removing – in the UK also – the requirement to register in these circumstances. If it was so important for the ICO to effect these changes before then, why keep it quiet?

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.

Filed under Data Protection, Directive 95/46/EC, GDPR, Information Commissioner, Uncategorized

The first time Parliament heard the term “Freedom of Information”

…if there is one matter on which I feel more strongly than another it is that in a democratic community the foundation of good government lies in freedom of information, freedom of thought, and freedom of speech: You can not have a country, which is governed by its people, wisely and well governed, unless those people are permitted access to accurate information, and are permitted the free exchange of their views and their opinions: That is essential to good government: It is quite true that if you grant that freedom there will be abuses: It is quite true that foolish people advocate foolish views: That is one of the many unfortunate corollaries

Although the past is a foreign country, some of its citizens can seem familiar: the quotation above is from Liberal politician Sir Richard Durning Holt, and was made in a parliamentary debate seven months short of a hundred years ago. It contains the first recorded parliamentary use of the term “freedom of information”. It was said as part of a debate about conscientious objectors to the “Great War” (Holt was drawing attention to what he saw as the unfair and counter-productive prosecutions of objectors). He may not have meant “freedom of information” in quite the way we mean it now, but his words resonate, and – at a time when our own Freedom of Information Act 2000 is under threat – remain, as a matter of principle, remarkably relevant.

I found the quotation using Glasgow University’s extraordinary corpus of “nearly every speech given in the British Parliament from 1803-2005”. I commend it to you, and, a century on, commend Sir Richard’s words to Jack Straw and his fellow members on the Independent Commission on Freedom of Information.

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.

Filed under access to information, Freedom of Information, Uncategorized