The Court of Appeal has handed down an extraordinary judgment (Buzzard-Quashie v Chief Constable of Northamptonshire Police [2025] EWCA Civ 1397) in which the Chief Constable of Northamptonshire was forced to admit civil contempt of court, after camera footage, which the police force had repeatedly insisted, including before the lower courts, and also in response to an express order of the county court, did not exist, was found to exist just before the appeal hearing.

The appellant/applicant, Ms Buzzard-Quashie, had been arrested and initially charged with an offence in 2021. The arrest had involved three officers, all of whom had deployed body-worn-video cameras. Ms Buzzard-Quashie had complained about the arrest very shortly afterwards, and had sought copies of the footage. Although the charge was dropped, the force made only “piecemeal” disclosure, before determining that there was no further footage, or what there had been, had been destroyed.

At that point, she complained to the Information Commissioner’s Office, who told her that it had told the force “to revisit the way it handled your request and provide you with a comprehensive disclosure of the personal data to which you would be entitled as soon as possible”. (Here, the court – I believe – slightly misrepresents this as an “order” by the ICO. The ICO has the power to make an order, by way of an enforcement notice, but it does not appear to have issued a notice (and it would be highly unusual for it to do so in a case like this).)

The force did not do what the ICO had told it to do, so Ms Buzzard-Quashie issued proceedings in the Brentford County Court and obtained an order requiring the force to deliver up to her any footage in its possession or, if none was available or disclosable, to provide a statement from an officer “of a rank no lower than Inspector” explaining why it could not. It also required the force to pay her costs.

Remarkably, the force did not comply with any element of this order. This failure led to Ms Buzzard-Quashie initiating contempt proceedings in the High Court. At that hearing the Chief Constable, in evidence, maintained that that a full search had already been performed; all the footage had been produced; no other footage existed; and he was not in contempt. The judge found that Ms Buzzard-Quashie had not succeeded in establishing to the criminal standard that the Chief Constable was in contempt.

Upon appeal, and just before the hearing, primarily through the efforts of Ms Buzzard-Quashie and her lawyers (acting pro bono), the force was compelled to admit that footage did still exist: its searches had been manifestly inadequate.

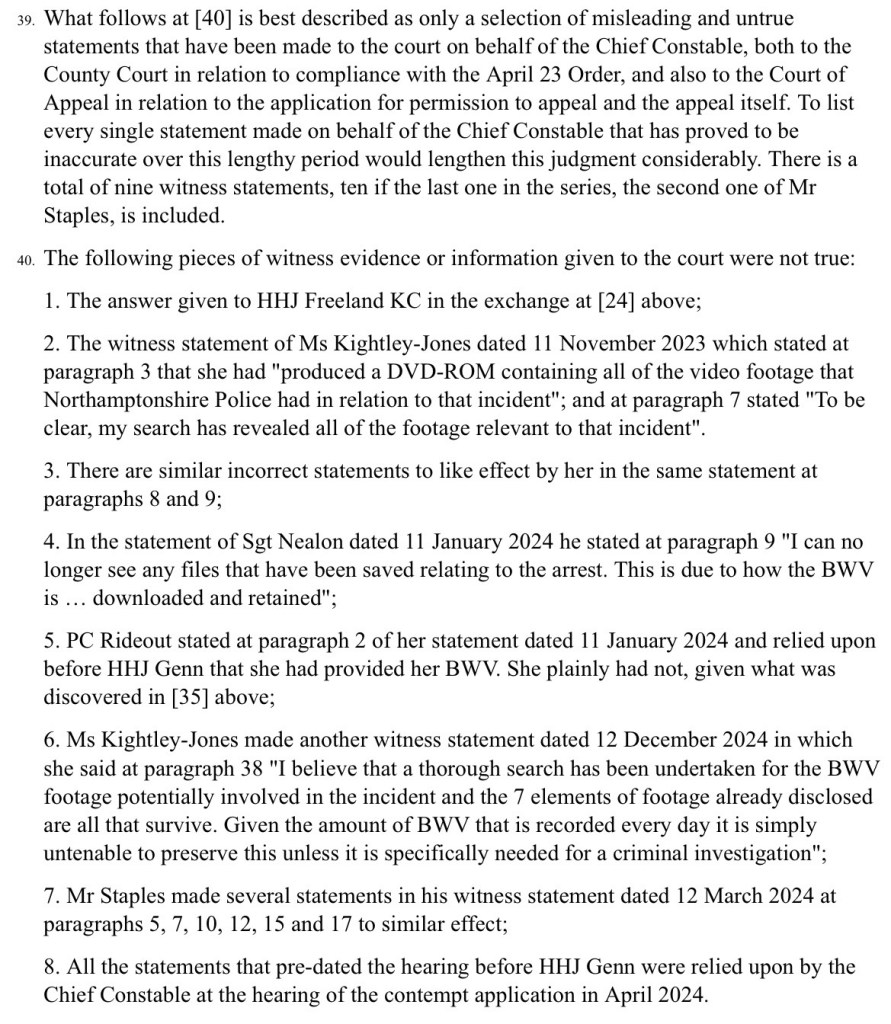

The CoA found that eight pieces of information and evidence (and this was “only a selection”) had not been true, and that “the Chief Constable had not only failed to comply with the [County Court] Order in both substance and form, but had advanced a wholly erroneous factual case before that court, and before this court as well”. Ms Buzzard-Quashie clearly succeeded in her appeal.

The judgment records that the issue of sanction for the contempt found “must wait until the next round of the process”, which presumably will be a further (or perhaps remitted) hearing.

There are any number of issues arising from this. It is, for example, notable that the data protection officer for the force was involved in the searches (and, indeed, she gave the initial statement that the County Court had ordered be given by an Inspector or above).

But a standout point for me is how incredibly difficult it was for Ms Buzzard-Quashie to vindicate her rights: the police force, for whatever reason, felt able to disregard both the statutory regulator and an order of a court. She and her pro bono lawyers showed admirable tenacity and skill, but those features (and that pro bono support) are not available to everyone. One welcomes the fact that all three judges noted her efforts and those of the lawyers.

The force has referred itself to the Independent Office of Police Conduct, and the Court of Appeal has reinforced that by making the referral part of its own order.

In this post I’ve tried to summarise the judgment, but I would strongly encourage its reading. The screenshot here is merely part of the damning findings.

The views in this post (and indeed most posts on blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.