Complacency about data protection in the NHS won’t change unless ICO takes firm action

Back in September 2016 I spoke to Vice’s Motherboard, about reports that various NHS bodies were still running Windows XP, and I said

If hospitals are knowingly using insecure XP machines and devices to hold and otherwise process patient data they may well be in serious contravention of their [data protection] obligations

Subsequently, in May this year, the Wannacry exploit indicated that those bodies were indeed vulnerable, with multiple NHS Trusts and GP practices subject to ransomware demands and major system disruption.

That this had enormous impact on patients is evidenced by a new report on the incident from the National Audit Office (NAO), which shows that

6,912 appointments had been cancelled, and [it is] estimated [that] over 19,000 appointments would have been cancelled in total. Neither the Department nor NHS England know how many GP appointments were cancelled, or how many ambulances and patients were diverted from the five accident and emergency departments that were unable to treat some patients

The NAO investigation found that the Department of Health and the Cabinet Office had written to Trusts

saying it was essential they had “robust plans” to migrate away from old software, such as Windows XP, by April 2015. [And in] March and April 2017, NHS Digital had issued critical alerts warning organisations to patch their systems to prevent WannaCry

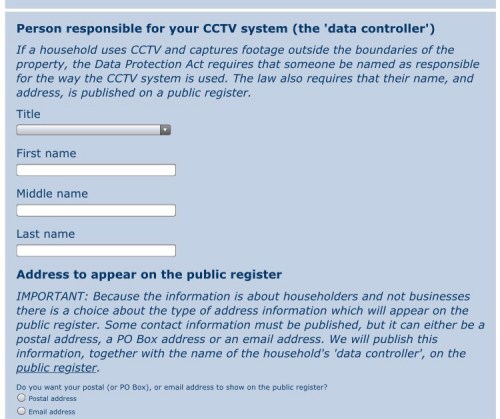

Although the NAO report is critical of the government departments themselves for failure to do more, it does correctly note that individual healthcare organisations are themselves responsible for the protection of patient information. This is, of course, correct: under the Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA) each organisation is a data controller, and responsible for, among other things, for ensuring that appropriate technical and organisational measures are taken against unauthorised or unlawful processing of personal data.

Yet, despite these failings, and despite the clear evidence of huge disruption for patients and the unavoidable implication that delays in treatment across all NHS services occurred, the report was greeted by the following statement by Keith McNeil, Chief Clinical Information Officer for NHS England

As the NAO report makes clear, no harm was caused to patients and there were no incidents of patient data being compromised or stolen

In fairness to McNeil, he is citing the report itself, which says that “NHS organisations did not report any cases of harm to patients or of data being compromised or stolen” (although that is not quite the same thing). But the report continues

If the WannaCry ransomware attack had led to any patient harm or loss of data then NHS England told us that it would expect trusts to report cases through existing reporting channels, such as reporting data loss direct to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) in line with existing policy and guidance on information governance

So it appears that the evidence for no harm arising is because there were no reports of “data loss” to the ICO. This emphasis on “data loss” is frustrating, firstly because personal data does not have to be lost for harm to arise, and it is difficult to understand how delays and emergency diversions would not have led to some harm, but secondly because it is legally mistaken: the DPA makes clear that data security should prevent all sorts of unauthorised processing, and removal/restriction of access is clearly covered by the definition of “processing”.

It is also illustrative of a level of complacency which is deleterious to patient health and safety, and a possible indicator of how the Wannacry incidents happened in the first place. Just because data could not be accessed as a result the malware does not mean that this was not a very serious situation.

It’s not clear whether the ICO will be investigating further, or taking action as a result of the NAO report (their response to my tweeted question – “We will be considering the contents of the report in more detail. We continue to liaise with the health sector on this issue” was particularly unenlightening). I know countless dedicated, highly skilled professionals working in the fields of data protection and information governance in the NHS, they’ve often told me their frustrations with senior staff complacency. Unless the ICO does take action (and this doesn’t necessarily have to be by way of fines) these professionals, but also – more importantly – patients, will continue to be let down, and in the case of the latter, put at the risk of harm.

The views in this post (and indeed all posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.