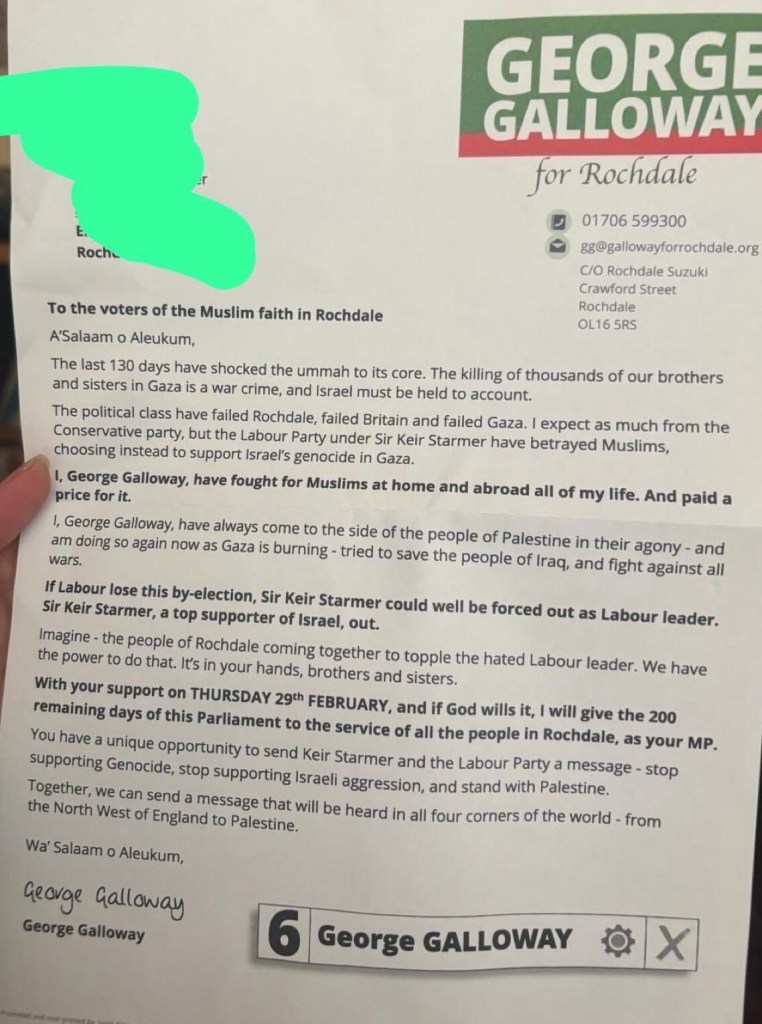

As electors went to the polls in the Rochdale by-election on 29 February, a few posts were made on social media showing the disparity between letters sent to different electors by candidate George Galloway. An example is here

On the face of it, Galloway appears to have hoped to persuade Muslim voters to vote for him based on his views on a topic or topics he felt would appeal to them, and others to vote for him based on his views on different topics.

It should be stressed that there is nothing at all wrong that in principle.

What interests me is how Galloway identified which elector to send which letter to.

It is quite possible that a candidate might identify specific roads which were likely to contain properties with Muslim residents. And that, also would not be wrong.

But an alternative possibility is that a candidate with access to the full electoral register, might seek to identify individual electors, and infer their ethnicity and religion from their name. A candidate who did this would be processing special categories of personal data, and (to the extent any form of automated processing was involved) profiling them on that basis.

Article 9(1) of the UK GDPR introduces a general prohibition on the processing of special categories of personal data, which can only be set aside if one of the conditions in Article 9(2) is met. None of these immediately would seem available to a candidate who processes religious and/or ethnic origin data for the purposes of sending targeted electoral post. Article 9(2)(g) provides a condition for processing necessary for reasons of substantial public interest, and Schedule One to the Data Protection Act 2018 gives specific examples, but, again, none of these would seem to be available: paragraph 22 of the Schedule permits such processing by a candidate where it is of “personal data revealing political opinions”, but there is no similar condition dealing with religious or ethnic origin personal data.

If such processing took place in contravention of the prohibition in Article 9, it would be likely to be a serious infringement of a candidate’s obligations under the data protection law, potentially attracting regulatory enforcement from the Information Commissioner, and exposure to the risk of complaints or legal claims from electors.

To be clear, I am not saying that I know how Galloway came to send different letters to different electors, and I’m not accusing him of contravening data protection law. But it strikes me as an issue the Information Commissioner might want to look into.

The views in this post (and indeed most posts on this blog) are my personal ones, and do not represent the views of any organisation I am involved with.